- Home

- Pierre Turgeon

Hitler's Boat Page 2

Hitler's Boat Read online

Page 2

The fall’s vaporized water refreshed our sun burnt skin. “Look! It will be all yours!” He let go of my ankles to embrace all the pylons with a wide gesture, with high voltage cables running at the end of their arms of truss; all this material that he had bought thanks to a loan from the bank. Jumping from one tree to the next, the ravens preceded us with their dissonant cries; drops of water fell from the still wet pines into the pond, their circles not easily distinguishable from one of the long legs of the harvestmen’s jerky strides. I ran on the wet grass. The sun sparkled over the tips of the pines and the black and yellow pansies’ petals surrounded the porch like a velvet carpet.

In the evening, my father, who wanted to start up his own business, was experimenting at the station. He was attempting to improve the turbine by curving the blades and putting them closer together and at midnight, he would try out his prototype, which often led to power failures. The nanny would light a candle in preparation, and we would bathe in its languishing, oscillating light until the resurrection of the 60 watt light bulb: a bright flash that would rip me away from my dreams and would reconstruct the living room around the filament standing in its inert gas. Angels would cross the walls, lying in the air with enigmatic smiles under their twinkling hair; beavers would smack their tales on the carpet with a crash. Thus, my childhood was spent in modern amazement. My dad was a carrier of light, a Lucifer whose magic would light up the windows of the department stores.

My war name of von Chénier I took from my ancestor, Jean-Olivier Chénier, who John Colborne’s soldiers killed with two bullets as he was running from the Saint-Eustache Church, which was engulfed in flames. Because he was wasting his time in the med faculty, my heroic and hypothetic great-great-grandfather (our relation is still somewhat foggy) would have been better off taking Carl von Clausewitz’s classes, who taught at the Berlin military school from 1818 to 1830. The Prussian general’s theories would have taught him that during war “the probabilities of life replace the concept’s extremes and absolute,” sparing him the military humiliation of shutting himself up with his four hundred men in a catholic temple devoted to the second century’s martyr, who died asphyxiated with his family inside a brass barrel under which a fire had been lit.

Even though he was a poor strategist, the independence chief did not deserve the Church’s refusal to bury him in sanctioned grounds. Yet he did so, dishonoring himself by trying to humiliate one of our rare heroes. Witness to the clerical and warrior bunging, Lord Durham, previous British ambassador during Alexander V’s court in St. Petersburg, and named dictator of Canada by a young Queen Victoria, he assured us we had no history, that we did not exist, and that our essence was purely virtual, the crown had to eradicate it to avoid more troubles in North America. This old defeat humiliated me each time I heard an order barked in English to the red tunics sporting black berets who stood tight rows on the grounds of the Plains of Abraham, in front of the monument of Wolfe, our conqueror, also in front of my grand-father, Colonel Perkins, and that I was not allowed to approach since the separation of my parents. I, along with my comrades, began to believe in a country that would belong to us, which I called Quebec.

That idea did not come from my father. Despite his Anglophobia, he was still a federalist and an antinationalist. He plugged his ears to his feelings of inferiority; he stayed deaf to the sounds of the independence sirens. But this Laurentian Odysseus wanted his own destruction, and he was dragging his son along with the wreckage.

While in this Berlin that is falling to pieces and where folks practiced the hatred of Jews, he was teaching me the hatred of our own people. This condemnation presented a prohibitive and metaphysical character, as it only targeted our provincial, even medieval, accent or the fatal corrosion of our words by English, or the syntactical deformities of our sentences, but also a lack of soul. So, this was a people come from sub-humanity, from cattle psychology, from marsh sociology, from a history of stupidity!

Even the French, he had the habit of saying, even a worker, poor and drunk, could express himself a thousand times better than the best Canadian orator. He would not deny that foam floated on this muck, that a thin intelligentsia would be on top, but it was much closer to a bowel movement than actual mind work. My father’s cartography placed me at equal distance between inanity and void: either I knew what I was and I belonged to a herd of donkeys, or I would escape the pen, but no one - I first - would be able to tell what I was anymore.

Foreigners wouldn’t find grace in his eyes either. From the insolent, uncultured and awkward English, to the narrow-minded, fanatical, cruel and cold German, passing by the impious, drunk and petty French, the greedy and cheap Jew, the fat and disgusting American, it was humanity as a whole he would reek thunder upon during meals, with an eye fixed on an inaccessible ideal and the other on the one that exasperated him through an elbow placed on the tablecloth, by a mouth that dared to chew. To escape his wrath and his slaps, I would turn myself into a statue, but absolute immobility would only agree with him for a moment, since I was to ingest the various foods placed on different plates, my stiff muscles condemning me to spill glasses, pitchers and saucepans. I would hold my breath as the stain, as outrageous as blood on the Shroud of Turin, got bigger and bigger, moving towards the edge of the table, following the fickle topography of the salt shakers and the tablecloth’s folds, to finally drip on the kitchen’s linoleum: and so with the liquid puddle mixed the dry banging of drops against nape.

From the bottom of my triple abyss, human, national and familial, how could I have formulated a valid thought? I could not! Only the rosary occupied my lips to tasks that were not profane. Jesus dead on his cross! I spent my childhood adoring a corpse. But the true corpse was myself, and not the Christ made of plaster and bought during a pilgrimage to Sainte-Anne, nailed by my father’s stare that would not kneel next to me, but rather leaned against the wall in the hall to rectify with a kick to the back of my thighs at any slackening of my devotion.

More than religion, it was military history that he proposed as a model to rip me away from our depravation. On the living room walls, portraits of Napoleon, Mussolini and Hitler contemplated their prey as they ripped through them with their teeth, as well as the supposed prominence of their jaws. A few havens - Beethoven, Hugo, Péguy - completed this pantheon of rare humans to have achieved thought. I was perhaps condemned to become fatal and fascist. But I was also learning the taste of freedom.

I realize that I am darkening my father. Grace be given to him: he taught me to spell, for which he felt a fanatical respect. His dictations were punctuated with ruler strikes on the fingers at the slightest error and I can still feel his hot breath on my neck as he bent down to better read in my notebook as I was hesitating on the letters to write, but not too long because inaction was also punished.

Admirer of the Führer, he signed me up for private German classes, which allowed me to hide from the friars at my college the religious doubt I would write down in my diary. Thus, it was with Nietzsche’s words that, in 1935, I admitted to myself that I could not believe in God anymore. “Gott is tot,” I screamed as I threw a large-rimmed hat soaked in ideas as much as in sweat through my student-dorm window, flying and following an elliptical trajectory before dropping on the snow.

The relative and the zero triumphed. With the Aquinian doctrine of numbers, the City of God was crumbling, like San Francisco in 1905, full of speculators exploiting the course of theological changes, not knowing that the ground was slipping away from underneath their feet. Through this breach, the total war was already being engulfed, art for art and “to live is to sell.”

When I had the audacity to expose my Kantian critical proofs of the Divine existence, the friars locked me up in a small underground, in the middle of what was a hole that led to the sewers. They had placed my typewriter on a wobbly table. Surrounded by the nauseating smell, I had to write up an act of contrition with humility. I was afraid the naked light bulb on the ceiling would

die out; I would then have to grope around for the door, trying to avoid the gaping hole without any other point of reference other than the freshness and smell escaping from it. I wrote nothing at all and they had to set me free.

Behind the glass doors of the boudoir that served as his dispensary, my father sat, deformed and multiplied by the cuts in the windowpanes. He was wearing a blue Marian uniform and an arm piece with a swastika. I was filled with shame. A cigar in his mouth, he was dreaming out loud. He would finance, he said, the printing of tracts for the National Christian Socialist Party. With friends, he would create a New Order. He brought me to assemblies. The marching of boots chanted the patriotic speeches in the parish halls: excited salutes, shirts wet at the armpits, plaster Sacred Heart on a pedestal on a Corinthian molding, with its Jewish arms in the air to bless his anti-Semite followers, bloodstained cassocks from the blows given by the flocks to the Communists freshly arrived from Poland or Italy. It all seemed even more ridiculous and pathetic since these tavern pillars were giving into the British branch of Nazism.

This political fever was a release valve for my father’s rage at seeing his company crumble under debts. Fascism consoled his despair. The only thing sacred he knew was money, which flowed everywhere at an infinite speed, and the trajectory and mystery of which drew the universe, like marbles coming and going on paper. “Since I refuse to sell to them, he repeated, the English are killing me.” When the bank reminded him of the loan, he emptied the drawers in his desk and burnt the plans of the new turbine, waited for the bailiff to fix the seals and then, without a word, his jaws tightly closed on his chewing gum, and he went down to the engine room. He grabbed the alternator’s high-tension cable and charred to death in his tweed suit that smelled burnt. In the tension change of my room’s light bulb, I could feel my father twitch under the 150,000 volt electric shock.

The world was leaking like an endless suffering. Thought in flesh, like a hook in a fish: pull the line patiently, the swift silver flash jumping over the foaming water, and the INRI Christian mystery, the virgin uterus. Touch his wounds; my father was back from the dead. With his calm and serene voice, his love fixed the order of the planets. He was crying beneath the linen shroud. Violence rolled at the back of the sky: the stars were cries. The calm water beneath the cormorant’s sharp beak, sunfish were offering their entrails to the fateful omens. My father wrapped a black and white cloth around his left wrist; his smile resembled the slash of a sword in a bag of flour. In the cemetery, the bugs assaulted me on that torrid night of July.

Militiamen of the People’s Army of Quebec crammed themselves on a raft: busted three-cornered hats, uniforms ripped to shreds and archaic rifles. On the grey beach, a block of foot soldiers like a porcupine of bayonets was waiting for them. A sharp order: Fire! And the craft held nothing but corpses that the current was sweeping away towards the sea under the fog. But the killers did not leave their post, in a unanimous gesture, they reloaded their weapons because another raft was now emerging, or maybe it was the same one with the dead that the fog would have mysteriously resuscitated. Fire at will! This scene repeated itself as relentlessly as the waves that would come to soil with red water boots of the wigged officer, my maternal grandfather, who brandished his sword to order the successive discharges.

In the celestial Quebec grand-place, translucent slabs made of a milky glass, would light up red when you walked on them, on Sundays, during family walks in eighteenth century costumes: bodice dresses, crinolines, sheepfold embroidered silk parasols and velvet frock coats with trimmings. Under each slab, lit from the inside by a light bulb, the severed skull of a combatant was telling his tale and that was there that I listened to my father’s wax head, crying with truth, he confided in me that we were humans, also. No more, no less.

What a strange irony for the Quebec freedom fighter I had become: Colonel Perkins, my maternal grandfather who resembled General Wolfe, at least, in the few portraits we kept from the conqueror of the Abraham Plains. I myself had red hair and could speak English. For many, this hybridity was a sign of duplicity. “Sell out! Traitor!” they would say to me. Far from alienating me from the national cause, these insults just increased my fervor as if my zeal could erase my original sin. It was my father’s race that I wanted to glorify and liberate; the race that my mother’s family mocked through endless litanies, and which I had to bear in silence now that my mother had taken me back. “Frogs. Always grand gestures. Such emotions! Chatterboxes! No sense of business. And on the battlefields? Cowards. Cowards!”

My grandfather must have known what he was talking about since, in 1917, he had commanded a platoon in charge of restoring order in Quebec after the riots against conscription. He had the courage to order his men to fire on an unarmed mob. Fifteen dead on the pavement. “French Canadian cowards!” he said, squinting his pale blue eyes behind the cigarette smoke coming up from his rounded lips.

On a spring morning when the Colonel was giving training commands to his troops, a huge icicle fell from a cornice and outright killed him. Obviously, God’s vengeance against this Catholic eater. A widower, he left all his fortune to his only daughter, Virginia, who could continue sending both of her sons to boarding school, one Lutheran, the other Jansenist.

No more than her widowhood, this death didn’t change much about her existence. She continued to have her vaporous beauty photographed in the Parliament gardens. I guessed her lover by the looks she would give the lens; on the bound snapshots she would show us during holidays.

At twenty, Perceval embraced his military career. Insolent face, fake Parisian accent, cricket, tennis champion, tea drinker, reader of Lewis Carroll, hunter and cold-water swimming enthusiast, he invited me to take part in a canoe crossing of a frozen river with him. In 1935, he left us briefly for the Far East and the Balkans as a military attaché and information officer.

The same year, I moved to Montreal where, with the help of a professor, I found a job as a journalist: dogs being run over, mediums and ectoplasm, smell of ink and sweat as the deadline approached, three pages a day for the little miseries of the little people, my name printed on thousands of copies. I would scrutinize human nature through the help of the brief news: murders, fights, drowning, riots; my ear glued to the phone, I would wait for the breathless hush of the night to calm down. On the river, dawn would crack just like a nut.

In my nightmares, naked bodies would form the letters of my articles: here a woman was straddling her lover who, standing up, extended his arms forward to represent an F; a young girl prostrated in front of an old man formed an E. Thousands of sweaty acrobats were contorting themselves into the letters of the alphabet, and a surge of Lilliputian orgasms determined the evolution of my narrative. I examined with a magnifying glass the faces of this human tide: mouth opened, tongue hanging out and wriggling, traits deformed by pleasure. The words were writing themselves, they pulled me, tied behind a chariot through a crowd that covered me in gibe and spit, arms pulled forward, wrists broken over the keyboard by invisible shackles.

With the help of a typographer, I illegally published a nationalist paper that we would make at night. I distributed copies at the gate of factories, ready to run for it if a policeman came near. After the invasion of Austria, it was obvious a crisis was brewing in Europe. I wanted to avoid my people sacrificing themselves again for the British Empire.

In August 1938, I spoke in a meeting at the Gesù. Around two hundred people came to listen to the New Nationalism speakers. From the stand, I argued for a new Quebec republic, layman and neutral. In the back of the room, agitators from the National Unity of Canada Party in swastika uniforms, jeered: “Communist! Go back to Moscow!” one of them said. Other opponents, Maurrassian nationalists, who should have opposed the Nazis’ federalism, joined them by chanting: “Damned atheist vermin!” The booing forced me to get off the stand without being able to finish my speech.

At the back of the room, a woman of about thirty, wrapped in a shawl with a bell

hat on her head, was waiting for me. “You’re right!” she said in German. “But it’s not enough. You need numbers.” I dragged her outside the hall saying, “And even if the world was full of demons, we would succeed anyway!” She burst into laughter and answered, “Luther! My father is a pastor in Bremen. I know all those psalms by heart.” In a clumsy German, I asked if she was interested in our national cause. “I have enough of mine! No, I came to rehearse for a concert later on.” Amateur pianist, she earned a living as a secretary for the Montreal German Railway office. Her comrades were entering the hall that was now devoid of the crowd that had come to listen to the political debates. She invited me to come listen to her.

Instead of going back to my apartment on Saint-Denis Street, I went down to the port, and then walked along the Lachine canal. Barges were going up the locks to pick up cargo of wheat, cars and cannons from Detroit or Chicago. When I came back to the nearly deserted Gesù, the trio was playing Mozart on the stage where my “For a French-Canadian State” poster had been removed.

The pianist expressed the deep and gentle sadness of intimacy. Between each movement, her eyes would turn to the violinist before diving back to the keyboard, where fingers that I wanted on my skin were running, light as pleasure. She sang in silence, marking the pauses with a sigh that lifted her breasts underneath her red satin tunic. I listened enraptured, already vaguely in love with this Lizbeth Walle, whose name was printed in gothic letters on the program. Pale and thin, the skin of her face betrayed the slightest emotion as I deciphered her blood flow with a certainty I believed divinatory.

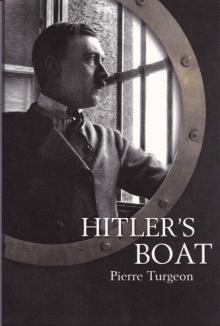

Hitler's Boat

Hitler's Boat