- Home

- Pierre Turgeon

Hitler's Boat

Hitler's Boat Read online

HITLER’S BOAT

HITLER’S BOAT

A Novel

Pierre Turgeon

Published by Transit Publishing Inc.

Copyright ©2010 Pierre Turgeon

The reproduction or transmission of any part of this publication in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, or storage in a retrieval system, without prior consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic production of the material, a license must be obtained from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright) before proceeding.

ISBN: 978-1-926893-56-3

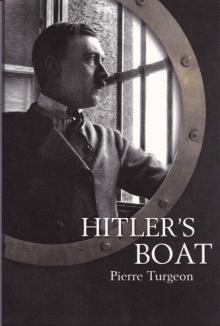

Cover design : Francois Turgeon

Text design and composition : Benjamin Roland

Cover photo:

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Transit Publishing Inc.

279 Sherbrooke Street West

Suite#305

Montréal, Quebec

H2X 1Y2

CANADA

Phone : + 1.514.273.0123

www.transitpublishing.com

Printed and Bounded in the United States of America

To my dad

But Man must devote himself to his country

To what use is revolt and regret?

If its image is painted at the Unicorn pavilion

Its bones can die on the battlefield

Tu Fu (712-770)

This cry, it is resumed into one word that each French Canadian will understand, after being so long asleep: “Soul of Old Quebec, awake!”

Adrien Arcand, Octorber 20th, 1933

Sunday night, the German radio, during a show destined especially to French Canada, announced that Hitler is offering it its full independence.

Jean-Charles Harvey, Le Jour, June 29th, 1940.

PART ONE

NOTEBOOK ONE

I have decided to stop waiting for the right moment to talk, because it will most likely never come. I will also skip the inspiration. I await no pardon, nor from God neither from my master, only the peace that comes from a sincere confession. After six years of war, I declare armistice and I sign my surrender without conditions, in Berlin, behind the broken windows of the Empire Broadcasting Company (Reichsrundfunk), all the Büro Concordia services having already fled for Dresde, which was broadcasting in India, Caledonia, France, Norway and French Canada. Dismantled telex, typewriters and boxes of documents clutter the entrance hall.

Arms filled with scenarios, folders and gramophone records, the secretaries hurry towards the trucks and cars that are waiting in the yard. Looking for colleagues that I used to see everyday down the halls or in the bunker so full of confidence, I push open familiar doors to see but one dust covered chair and to feel a cool breeze coming in through a broken window.

The violence of the Soviet artillery forced us, sergeant von Oven and I, to hide in the basement. There is no more coal left to heat up the chicory; we are smoking our last Juno. And now, since the generator has run out of fuel again, Von Oven is cursing as he goes out to siphon diesel from the destroyed Panzer. So I have a few hours alone ahead of me. I use this time to commit a modest sabotage, despite it being deserving of the firing squad, so that my story may live on; I am writing on the back of these documents I was given to microfilm, in German, to better camouflage this administrative Teutonic prose from which I hope to extract my own story.

Perhaps my text will make it out of the surrounded city. No one knows who will carry these documents out of the bunker after we will have photographed them in the last remaining operational studio in Berlin. Requisitioned by the Chancellery!

Shivering in front of the microphone even with my coat, hat and mittens, I repeat that the organists are fighting via their intermediary the French Canadians and that a closer look on the West front proves they are occupying the most dangerous sectors. Then, changing the broadcast frequency, I play the role of my character, Gustave Chénier, partisan of the Independent Laurentie, forced to hide in forests near Quebec to escape the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. I am supposed to be broadcasting from there, near my hometown, and not from the center of the Third Reich, from this city now surrounded by one hundred and forty divisions of Marshall Joukov, with fifteen thousand pieces of artillery.

I slept in the ministry’s basement; the enemy planes were hindering my sleep. How do I stop my right hand from shaking? This morning, I sent someone to fill the prescription for tranquilizers, specifying to go to Engel’s. He is the only one capable (everything will be ready tomorrow); even the SS central pharmacy has a hard time getting some, because the factories and labs have been bombed. Order and tightrope walking are two of my contradictory specialties. No one knows one’s face before one is born. The present is catching up to me. My corpse lays there, like rotten meat, a machine good for the scrap yard. The world has no other face, no secrets. Bliss and misery. The movement towards the mirror could accelerate if my situation became unbearable. I cannot bear myself anymore. Moses, it’s ghastly!

I hide what I’ve written in a black folder and then I hold it against my chest, under my jacket with a snap clasp belt. I sleep a little and I go down to the green room to join Hofer. Sitting in a Louis XVI sofa, he is burning the family heirloom of his master Gœbbles, whom he’d just seen at a meeting of the heads of department, in the clay stove, his muddy boots dribbling all over the thick Turkish rug.

The flames engulf photographs of the Doktor at age seven dressed in a sailor suit; they draw black stars in the middle of his elementary school report cards. Hofer’s pasty white skin, his small blue veins throbbing beneath his temples, his bloodshot eyes; all signs that he hasn’t been sleeping: a reflection of my own appearance.

“Exoriare aliquis nostris ex ossibus ultor,” he whispers, stuffing more paper in before shutting the cast-iron door. No, the avengers will not want our bones, because we will all be incinerated. A bomb explodes nearby. The walls vibrate. Some debris falls on the photograph lying on Hofer’s knees. With a swift movement of his hand, he clears the glossy surface. “Let us pretend that the color cameras our technicians promised us really exist. Let us make our suicide an act of propaganda. How would you do it?” I shrug and say, “I’d improvise.” He grimaces and clicks his tongue. “Tutt! Tutt! You need cyanide.”

Without a word, he takes a small vial from his tunic, the top cut off, and lets me smell the slightly burnt hazelnut aroma. Then he softly blows over the opening. “Listen to this music. I have already used it for my dog. Conclusive!” He bursts into laughter and looks at his watch. “I have to go retrieve more documents from the bunker. Make sure everything is microfilmed for tomorrow. Take all night if you have to.” Then with a wink and a smirk he says, “I will arrange for us to get the sacred mission of saving these documents. There will even be enough room for your wife.”

I avoid reminding him that I was the one who thought up the operation: redemption through literary eternity of Hitler’s intimate work, jotted down by three stenographs as he drinks the chalice to the dregs. After many texts spewed during his seclusion in the fortress, following the failed Munich putsch, he is once again inspired by this Götterdämmerung. I had suggested to Hofer that these Works of the Devil be taken out of the surrounded city and transmitted to posterity before the Soviets could destroy them. And why not carry them to my far, vast and frozen homeland? I had not anticipated the Führer would continue to write the ultimate verse and the penultimate maxim, forcing us to wait until the very last moment.

The

operation would allow us to survive while fighting in the ruins. When it comes to double-crossing, Hofer and I need lessons from no one. Neuman clicks his heels, another scribe who exchanged his writer’s cramps for the Hitlerian salute. The precise moment when he stiffly barks “Sieg!” he is permitted to, like all of his colleagues, dissimulate a fart. The horrid smell follows me all the way to the window. I press my nostrils between the two wooden boards that have replaced the glass.

Outside the moon is full. Frozen fog hovers over the surrounding lakes. Easter will come late in this year of 1945. Metal shards fly off in every direction at a supersonic speed: missiles, bombs, and tracer rounds. Panzerfaust. The racket stops for a moment and I hear the wind in a pine tree; I can breathe in the smell of wet sand coming from the gardens; my childhood games in Quebec beneath the shadow of Wolfe’s cannons. And then a single gunshot in the Tiergarten close by and the sound of the ricochet.

Hofer stands up in all his tallness and lifts his arms behind him like a crow ready to take flight, as Neuman stands on the tip of his toes to slide on the heavy military jacket Hofer has been wearing since his nomination as Obersturmbahnführer. Then they both leave for the bunker. I return to my office and continue to read the notebooks that pass through my hands.

Completely obsessed by the fate of his future corpse! Yesterday, Hitler sent Fegelein, his brother-in-law whom he suspected of wanting to give his funerary urn to the enemy, to the firing squad. Die, you filthy beast! Your agony is just being prolonged in a most obscene way. Was I the one to trace these lines? Yes, I who will finally show my true colors, in this defeat that is my victory.

I, who sees to the extinction of the hydra, something that has not been done. He could make it with Baun, his private pilot who is waiting for him in the Tempelhof underground hanger along with three long courier Junkers. Since the Biderman firm dug the longest labyrinth in history thirty meters below the chancellery’s court, I knew the Fürher had chosen as decor for the final act this cold and grey snake, coiled on itself, surrounding three ministries in its concrete coils, and able to receive within its entrails, its most loyal partisans: its last victims.

And I remember what he wrote in his Bavarian fortress twenty years earlier: “If things go wrong at the instant of supreme danger, I’ll disappear.” Simple men don’t kill themselves. He had probably already chosen his exit strategy. I tried to guess it through his aesthetic-political delirium.

I, Adolf Hitler, on the day of my fiftieth anniversary, I know nothing about nothing, not even if I am human. I have never directly seen my face. I have never spoken with any other organ than a tongue. Traduttore traditore. I am not sure I had parents, that people exist when I am not around, that I will disappear after my death. I would like to want nothing- to become heavy, frozen, and predictable. But there will always be a fraction of a second when I will not know what is going to happen. I have a nosebleed. I miss my dose of cocaine. It is dawn in Berlin. I await the Russians. I would like to be dispossessed. I would like to become a man without a history.

A mild conjunctivitis, most likely due to the wind and dust since there are a lot of ruins and debris in the yard. I was forbidden to read, but I do not follow this advice. I also refuse to wear a protective visor. Me, looking like an accountant! Obviously, the long hours spent studying maps are not helping. Before my incarceration in the fortress, I had broken my left arm, but I was able to recover the use of it through rigorous exercise. They want to steal my corpse, those traitors. And the Dachau ovens have been shut down! And those idiots from the Gestapo are letting everyone go: one moment, gentlemen! Allow me to go to the kitchen to fetch some ice for your cognac. And they disappear. The coffin is purring like a refrigerator behind my shoulder.

Ever since Stalingrad, I cannot get a hard-on. To distract myself, I would like to read all of Heidegger, or buy myself a medieval torture chamber. Do not tuck the tip of your tie in your pants, Kubizek would tell me in Vienna. Only peasants do that. At the height of my power, there was no longer a need for me to think. But now I have to and it is ruining my existence. But I still have treasures of cruelty, like Job on his mound of manure. And beneath that mound, a pre-prepared retreat. No one will notice. It is unfortunate these people were not good enough for me. I will take the subway at Grosse Stern station. I have a private entrance. A 10,000-meter gallery. No need to stick my nose out, to expose myself to captivity. They would stick me in a cage at the zoo.

The literary transposition can never hide the blatant reality. Has he gone completely mad? Perhaps. But the risk of his architect having built him an emergency exit that does not appear on official plans is too great. I transmit this information in codes during my show that Radio-Berlin insists on broadcasting to Canada, in a rigor mortis of its will for power.

“This is von Chénier speaking to you directly from Berlin. I do not apologize for scrambling your frequency to announce that the war is still going on, despite rumors of the contrary. Hidden for over two years in an abyss in front of Cap Eternité, our U-Boat is slowly making its way to the surface. Gurgling bubbles escape its steel hull, made to last a thousand years by a Bremen ship builder. Commander Kohl, who has already sunk twenty-three of your dinghies, informed us that his torpedoes are in perfect working condition. Remember people of Mingan, how your cabinets opened, how your peasant dishware shattered as it hit the rustic floor of your homes, how the thick and acrid air of your kitchen escaped through the shattered windows the night when, missing an escort destroyer, a torpedo hit the cliffs at the entrance of your insignificant harbor. History was flirting with you and you were trembling with fear. And so I tell you again, as on the glorious fall of 1941, people of Quebec, abandon your wives to the brutal caresses of our soldiers. Pack all of your belongings on ships and head towards the Old Country, up the majestic Saint-Lawrence, bigger than all the rivers in Germany, quickly before the U-Boat’s ruthless periscope breaks the sea-green waters and sends you to join the crews of Charlottetown, Rivière-des-Prairies and Cap Chat. To those who would believe this is merely a bluff on our part, I will simply say that yesterday, at the Paspébiac Hotel, the band played Glen Miller at the end Our network of informants also told us that Mackenzie King spent the night in the arms of his darling mistress and that you should not believe the lies your newspapers print about our beloved Führer, who is a good catholic with a special devotion to the Virgin Mary.”

End of transmission. On the other side of the Atlantic, in Montreal’s listening center they are probably already bringing the recording of my show to my half-brother, Captain Perceval Perkins, who will decode it. What the Allies will do with this information does not concern me anymore. I return home to go to bed with Lizbeth in the basement of our villa where I have brought down our mattresses. We are freezing right to the bones beneath the whitewashed vault. I risk a glance out of the covers and a shiver quickly sends me back into fœtal position. I would love a hot soup, some peat bog for the living room stove and a sleep that would not be disturbed by artillery. Night moves very quickly on Earth, changing its hemisphere of shadows and nightmares, it remembers the cider that was drunk in the time of King Arthur, the cries of baby tyrannosaurs being born in volcanic swamps and the first plant cell.

NOTEBOOK TWO

New shapes, new cosmogonies. I am a V1 speeding towards the stars before falling on the toilet bowl of a London WC. I am the secret weapon of an evermore secret victory created by mad scientists. My flesh burns like the fuel of an intimate hell.

Arriving in Canada, my ancestor was almost right out of the cathedrals. He found himself under a sulfurous moon, in a country where wolves gnawed the crosses in the graveyards and where the pagan cry of the raven chased away the angels. His wife, tied to a chair, which her bloodstained skirt covered, had her eyes gauged out and her nails ripped off by the Iroquois.

His world, that had taken him ten years to build after his escape from La Rochelle, after the crossing on the Capricieuse on rations of rotten lard and a horizon popula

ted by mosquitoes and Savages, fell apart. They tied him to a tree, while drinking the liquor they had stolen from a trading post, a young woman throwing firewood in the fire. Later, the burnt remains of Sir Chénier were exhumed for a good and proper Christian burial.

I was born in Quebec City in 1917, inside the fortified walls, in the shadow of the Saint-Jean gate. I played along the narrow streets, full of the smell of horse manure and filled with the echoes of trotting hooves, as though in the well-hidden hold of a fabulous stone galleon, birthing exactly where the river becomes sea, in transubstantiation as mysterious as the one of wine to blood. Gassed by the Germans, my father lost a part of his lungs, in the trenches of Ypres. I was three when he left the sanatorium and six when he came back from New York with a degree in electrical engineering, which allowed him to find a job as a junior director in a power station north of Quebec, in Saint-Gabriel, next to the Cartier River. This son of a doctor secretly thought of civil engineering as a social downfall, which he hoped to save by becoming rich at the head of a hydroelectric company.

My mother, Virginia Perkins, married him during a leave at the beginning of the war, breaking the ethics of mourning, since she had only been widowed from an Anglo-Canadian lieutenant for two months that had died next to my father during a bayonet charge. Feeling invested with the mission of consoling this protestant with magnificent red hair, he slipped the ring on her finger and loved her long enough to conceive me and then kissed her, leaving her and my step-brother Perceval, then five, to fulfill his duty as a hero of the Empire.

When he came back, he forbade his wife to see her family again and to speak a single word of English under his roof. This tyranny was not to last. Soon Virginia and Perceval left us to go live with my maternal grandfather. Hence, I was raised in French by nannies, while my brother was raised in English. During the holidays, I would spend entire days at the station, between the transformers and the huge sparkling spider of the rotary turbine, lying at the bottom of a fall. The catwalk shook, the machines’ high-pitched rumblings tore at our eardrums like a plane about to take off. Perched on my father’s shoulders, I held on tightly to his hair.

Hitler's Boat

Hitler's Boat