- Home

- Pierre Turgeon

Hitler's Boat Page 12

Hitler's Boat Read online

Page 12

“And why are you telling me all of this?”

“You would’ve found out when you went to Montreal. You would’ve known it was me and I don’t want any trouble with you either. And ever since you told me your story, I understood that the bastard was the same as the one from forty-five. The trouble with modern medicine: these Nazis are able to live incredibly long… So I have a present for you: the address where I shipped the microfilms in Berlin. Likely to a fake company name… Eckel und Schmidt, Import-Export. Here.”

O’Reilly gave him a matchbook on which he had scribbled the information and closed the trunk of the old Ford.

“I don’t know what the guy’s name is. But I’d advise you to take care of him before he takes care of you. He probably knows a lot of people who would do what I refused to. Especially since he thinks you had the time to read the contents of the microfilms.”

They shook hands on the platform of the station. The train rolled along the back country, punctuated by french-fry stands, topless bars, rivers as brown and as foamy as a Guinness, high voltage cancerous iron pylons, giant yellow ‘M’s under which the McDonald’s clowns distributed the minced meat wafers to their kneeling followers, minigolf courses surrounded by barbed wire and decorated with multicolored plastic flags, DC-3, Boeing; Constellations with their wings cut off and turned into discos, bushes wrapped in Glad bags. The usual magic sowed in a mess across the continent.

In Montreal, Christophe began to study German intensively. He had a knack for languages and he knew that in three weeks he would have the necessary basic vocabulary for a trip. These foreign sounds, through which an element of meaning passed, drawing another universe bit by bit, where night and fog took a sinister form when called Nacht und Nebel; where barbwire attached to pylons that curved toward a vast field of fine gravel could be defined, harnessed detainees dressed in striped jumpsuits and caps that were pulling road rollers that crushed the rocks and made walking easy on the boots, as they went up the center lane, from the administrative center, and they walked between the shacks, eyes riveted on the pines that moved lightly, at the back of the camp to the left fore of the crematory.

Could we free ourselves from the errors of history? Was the dream of national liberation – his and his father’s – not already skewed to begin with? In April 1933, the most brilliant partisans of independence had given troubling speeches, in the Gesù hall. The Hitlerian persecutions against the Jews? Imagine! His grandfather, the electrical engineer, was in the room with his two sons and he was applauding the speaker: “The bitch’s tail in Germany cannot be stepped on without its bark being heard in Canada.”

He had never really known his father. Of all the historical figures from Quebec, he was the one that had been pushed back into the shadows. Von Chénier only appeared in small characters in the footnotes of History books, perhaps because he personified the tendency of these people to betray themselves more than anyone else.

The central government had forcibly mobilized French Canada, which had massively protested the participation in the war during the referendum of 1940. The Prime Minister of Quebec, Duplessis, lost his right to oppose the war. He had been forbidden access to the radio in the middle of the electoral campaign. His opponent won. During the armistice, Camillien Houde, the mayor of Montreal, was freed from the concentration camp, where he had been withering away for four years for having publicly opposed the conscription. Medals were distributed to the heroes, pensions to the widows and von Chénier was consigned to oblivion. The victory that won over absolute evil would forgive the slight injustice that had been committed against its people.

His mother had an arrest warrant floating over her for being a native of an enemy country since 1939. But they could close the case no more on her than they could on his father. They had both disappeared and the official investigation stopped there. As for him, he decided it would start that day.

Without hesitating, and despite the fact that the purchase of the Helgoland had seriously eaten at his inheritance, he decided to leave for Germany. Nothing in his own country mattered to him anymore. You cannot command feelings. He was afraid of dying from a defeatist overdose. He had been taught fear and he did not know how to get rid

NOTEBOOK TWO

At Mirabel, a haughty, imperious voice interrupted the background piano: “Second call for the Lufthansa flight to Berlin.” This was a mass-produced airport female speaker: mass-produced in Taiwan. Nickel pipes formed cubes and pyramids over the bar where the beer went stale. About fifty country flags hung from the ceiling, forever immobile in the still air.

“We ask you to please buckle your seatbelts…” Elbow jabs from the neighbors. Honks, roars, take off! The passengers were sweating, while faking calm like the sensation of an elevator going up when the guts contract into nothingness. It was turning into a projectile that could not touch anything from the world below, neither women nor child, without tearing them to shreds.

Wearing a green Tyrolean hat, his neighbor to his left, a motivational psychologist from Ottawa, had been living in anxiety since his twin brother’s death. He was raising his children in English to take revenge on his separatist mother who had thrown a knife at his head. “That, that’s Germany,” an old man from Munich said pointing to a piece of rye bread on his plastic plate. Teutonic Eucharist. A Vietnamese man was pulling his hair out, fistfuls at a time; the flight attendant gave him a sedative. “It happens every time; a lot of people can’t stand the lack of space in coach.”

Christophe pushed the lock and the ceiling light of the WC lit up. His eyes red, he smiled to himself in the soap and cologne-stained mirror. Solitary connivance that was re-establishing his lost fragmented identity. Everything was changing, except for that wild and weary look in the mirror. Narcissist bewitchment.

Blue sanitizer spun at the bottom of the toilet bowl. Another sleepless night. There was not a clean spot left on the towel. He had to wipe himself with the others’ filth. When he came out of the cabin, a female passenger smiled at him. Green eyes, high cheekbones. She offered him a cigarette. “I’m an antiquary,” he said. “I specialize in Prussian earthenware. Very rare after all these wars. You?” Dancer. She was on tour in Germany.

A brief sleep restored his balance with the outside and lightened his dreams. The lights were turned off and the attendant unrolled the small screen. Burnt rubber and hardened arteries had the same smell in his mind like a tribute to pay to hasten towards cardiac arrest. He changed seats to contemplate the coast of Ireland, bleeding beneath the sun’s stabs. London passed under the right wing. Europe was rushing. Is there a single safe place, safe from the past? He was chasing it, like a burlesque mustached dictator in a video labyrinth.

Christophe was thinking about what the Irish had told him, to come up with a plan, to go from one small gear to the next. The stratosphere was yelling like a perforated lung over the apoplectic Alps.

The wind was shaking the plane; his neighbor was rubbing his groin with a careless index and raised his elbow to drink the last bit of cola: an ice cube was hiding a part of Mont Blanc. “Ladies and gentlemen, kindly refrain from smoking.” The landscape was coming up on them like a big hand coming down on the plane. The hangers on the side of the runway scrolled by at high speed. The red firemen, the yellow hills, the grey fuel tanks.

This was a science-fiction-like airport created by a Prussian architect. In the insomniac morning of jetlag, he saw his mother’s ancestral homeland. Berlin awaited him! He yawned behind the wheel of his rental Opel. Fifteen minutes and he would arrive at the Müller pensionhouse hotel. He hung his suits in the closet to smooth them out. A one-hour nap and this breaded and fried thing called a ‘Kotelette.’

It is here, on the steps of the Empire that the NATO steps stopped. Checkpoint Charlie. The Brandenburg Gate that perfectly encased the golden angel on the tower of victory in its arches. To the right, the Reichtag, a Soviet barrack, a mobile canteen, recently planted little trees, ditches full of scrap metal, mobile

homes, blue ribbons, red poles. In the parking lot, two hares were running beneath the cars. On the radio, Aida sang that she only loved her hero in the grave and that she wanted to warm him up in the entrails of the earth. Reuter Platz. The 17 Juli Strasse was lost in the horizon, larger than the Champs-Élysées.

Instead of the glass towers, he imagined his father’s Berlin of forty years earlier: gutted out kitchens where they ate in the rubble, the survivors addresses written in chalk on the walls, skating at the winter palace, the water collected from the fountain with a bucket, the cows in the streets, the requisitioned bicycles, the skeletons in the subway, the canal that was crossed on a raft, the straw sandals, the labors of the Wilhelm II Cathedral in the middle of Berlin, the ripped out pipes that hung from the walls.

To get to the address O’Reilly had given to him, he crossed the Tiergarten by foot, under the dark bolts of the naked trees against the cold October sky. Since his departure from Montreal two days earlier, he had only slept a few hours- a light and feverish sleep. He had ripped so much skin off from around his nails that a lot of his fingers were bleeding. His ulcer was burning, despite the gulps of hydroxide he drank directly from the bottle that he was holding like a weapon inside his trench coat pocket. To chase the pain away, he exercised breathing slowly through his lips, which were sucking in the air that smelled of mud.

Against the reddish and sandy soil, he imagined Lizbeth under the flash of the phosphorus bulbs or bombs, photographed underneath the same oaks while she attempted to flee with von Chénier. This Berlin that would become their grave.

Suddenly, at the end of the asphalt path, between two bushes, a grey form roared toward him, before bouncing off the grilled fence separating them. The furious barking of the wolf dog echoed until the dry order that was barked by a Soviet guard who had been leaning on the fence for a minute to look at him with his expressionless eyes under his fur hat. Then he turned back and resumed his goose-like mechanical walk, in front of a gigantic image of himself: the thirty meter-high statue the Russians had erected to the glory of their soldiers, right in front of the Brandenburg Gate, and where the Siberians kept the sacred flames and the young Asians swept the ground.

He should have died then, he thought, at the end of a long walk on Unter den Linden Avenue, heading for Moscow, stepping past the squabble, not stopping at the soldiers’ warnings, to a final fall, face against the sidewalk: his inner night turning white.

He had made a mistake. The address of Eckel und Schmidt VG was really on the left at the end of this road, but to the East. Back to the Opel. Two hours later, stopping at Checkpoint Charlie, in front of the reptilian mask of a Feldgrau border agent who was moving a mirror mounted on a buggy under the car, making sure the books on the seat were for Christophe’s personal use only, that the onboard radio was only for receiving and not emitting and that he was receiving the twenty-five marks for the twenty-four-hour visa the RDA granted.

It came from the vital body, without eyes or ears, only muscular and nervous, with the rhythm of blood to the mouth. There was no means to stop, to stand still. The Shapeless was changing every other second, taking a name and a hat to salute him with a kepi and signaling him to move forward. To the East like to the West, the puppets did not stop parading to give him emotions.

He was pulling on rubber heads and he was looking for his hand, which was shy due to its nudity, pointed to his temple with its index, and he would start laughing, alone behind the wheel. Oh! How he loved this autumn day when the cold seemed to come from the blinding sun! Lost, parked, his nose buried in maps, he looked up to see an Oriental walking towards the car as if she was the location he was looking for on the millimeter grid. At almost twenty years of age, she was short, tanned and dressed in dirty jeans and a pink scarf holding her frizzy hair up over her doe eyes.

She leaned on his car door. Yes, she knew the neighborhood well. She agreed to be his guide. She turned around and let out a cry. Her three companions came out from behind the truck. All quite young. Abdoul wanted to study engineering. Sélim was a guitar playing road worker and Saif, the strongest, was a truck driver with a big mustache. Then there was Fatima, their “sister,” who served as their German-English interpreter. Following their indication, Christophe quickly found himself in front of the address of Eckel und Schmidt Import-Export: an apartment building with its windows blocked by plywood, unoccupied because it was too close to the wall.

This quivering had to stop. The instructions were not coming in basic or in German, but in French, through the fingers, through the mouth. He was drifting. The wind had turned. He was paddling towards the faraway cave where his parents were embracing each other in the dark. The scene that repulsed and fascinated him, that he could not see because they had abandoned him, but that he hoped to re-enact with two corpses, two piles of stacked bones like in Pompeii. He was ready to burst into flames at the briefest stop of the magnifying glass.

The lead given by O’Reilly stopped here. Christophe questioned a neighbor that was getting into his car. “Amerikanisch?” he asked him. Sportsman’s running shoes. Tired, he did not clarify: Kanadischer. Why had this building been emptied? They closed that whole side of the road down. Too many tunnels. The last one even went through Hitler’s old bunker. Where are the old tenants? At the post office, they should know.

Long wait in a monumental marble hall. The Post’s Fräulein furrowed her brow and sighed impatiently and went to consult her superior. Long consultation in low voices over big notebooks. “We do not have a forwarding address,” she said as she came back to perch on her stool.

“And their mail?”

“We keep here for two weeks. They can pick up the remaining mail.”

Better than a PO Box, Christophe thought as he turned back. The Turks have to go back to the West after having their transit visas renewed by the East-German authorities. “A hundred marks every time,” Fatima told him. “If we don’t have a job next time, they’ll surely send us back to Ankara.” She looked at him, her eyes full of hope. He thought of hiring her as a guide and interpreter for a moment. Maybe. For now, he only wanted one thing: to go to bed to make up for the lack of sleep.

He dropped them off at a subway station. Fatima invited him to visit her in Kreutzberg. When he was about to fall asleep, Christophe saw von Chénier enter his room, dressed in a richly decorated suit. His face in the shadows. Egging him on in a soft voice to continue his research. Lifting the golden strike of a Kronenbourg to his health, its buck shimmering on the bedside table’s yellow tablecloth. I wanted to conquer this city, his father explained. Between the two of us, we still can. I want you to give me my peace, and for you to restore the honor of our name. But he, Christophe, had no son. When he would die, everything that was confined in his memory would disappear, including the present. Those faces that brush by in staircases or when gazes cross each other like leaves the bad weather would blow away. Here, in this bed, he was looking at himself, the pale hero of an unborn nation.

The next day, he found Fatima in a furnished room of Kreutzberg where she lived alone. The air was cold, despite the incandescent coil of a heater. She was freezing in her t-shirt that fell over her tapered jeans which left her ankles naked, as she rubbed her round mouth with her wrists sporting many cheap quartz watches like bracelets. Tiny tin staples pinched her ears. Her big eyes widened beneath the scarf that cleared her forehead.

“Can you come with me to the grocery store?” she asked.

A great force suddenly possessed him. The time of fluid hesitation and visceral anguish was over! He was becoming a tiger, his stride lengthened; he felt he would be able to kill in joy. He knocked a pebble with his foot: it hit a red tulip that shook and lost a petal.

On the wet grass, the shadow of an oak was sinking in the lamppost’s light. As he went forward, the branches moved to the left. He tightened his fists in his blazer, protective nest of Italian leather, around his navel, behind which that beast was leading him to follow this Ottoman that

rocked her hips on the overly high heels of her cowboy boots. She turned and smiled at him with her small, regular teeth. He was carrying pineapples and two cartons of milk in a plastic bag.

How could he court a twenty-four year-old Turkish girl who just had to close her eyes to be in Ankara, in the great villa her father Colonel Saïd Nursi built behind the Atatürk Mausoleum, and in her ears the trumpets of the guard relief in front of the square column? He felt a prickle on his lips, like after anesthesia. Fatima appeared in a spark of intensity, a reality that tore tears of admiration from him. She was lying on her bed. His hands fell on her like gulls on the sea, she said again, and his pleasure began to rise.

In the morning, he explained that he needed an interpreter to help him in the research he intended to do on a Canadian historical figure: André Chénier, also known by the name of von Chénier who died in Berlin in 1945. They would have to consult archives. Contact different ministries.

“Who is he to you?” she asked.

“My father, a man who made a mistake. And who tried to redeem himself.”

“When a father gets lost,” she replied looking at him intently, “it’s often with his son, no?”

They fought against a freezing wind to go eat at the Kurfürstendamm McDonald’s. “In Gogol’s Dead Souls,” he told Fatima, “there is a Russian character named MacDonald.” He swallowed the meat patty. “Ite missa est.”

They were telling each other the humiliations of their respective people while researching the halls of the ministry, inquiring with certain government agents, photocopying documents and examining the area’s city plans.

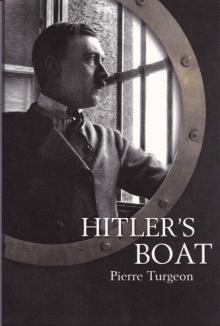

Hitler's Boat

Hitler's Boat