- Home

- Pierre Turgeon

Hitler's Boat Page 13

Hitler's Boat Read online

Page 13

“I’m thirty years younger than you,” she was saying. “But you’re naïve! Blond, thin and hard. Like the blade of a knife. Like a boy I loved in Ankara. The same metallic gaze. He planted bombs, too. His exploded between his hands. In an airport. He was a Shiite. Because of him, I can’t go back to finish medical school. I’ve been labeled a terrorist.”

To cheer him up, she dragged him on the Kurfürstendamm, where they listened to the city’s neo-Babylonian twitter, watching for its ghosts. In the discos, the pink fluorescents snaked over the dancers; the waitress rocked her hips against the cash register. Immense heartbroken city, but with a stomach of steel that could swallow everyone. Check, please! Sign it! “Everybody is signing it!” said Fatima, leaning on a plastic palm tree, dressed in a jacket made of two pieces joined together by laces on either side. When she bent forward to light up from Christophe’s lighter, he could peek at her left breast.

“Don’t hesitate to become a killer,” she told him, “take anyone and twist their neck. In school, I defended my ideas with scissors.” She climbed the ladder that led to the dance floor, and every sway of her hips, forced by her too tight skirt, showed him the line of her pantyhose which followed the curve of her thighs under the fabric, up to the next line, more secret.

It opened the path of his desire.

She cried to him over the music: “Don’t think about all those who are dead. Do you know what they want from you? That you taste, that you enjoy and tell them all about it.”

She explained she was looking for a country of refuge. What did he have to offer her? She caressed the nape of his neck. “You could get me into Canada?” she asked. He burst into laughter as he unbuttoned her dress. He laid his head on her chest and plugged his ears with her patchouli-scented breasts. Ready to commit crimes to caress her mane falling on her back that made him salivate.

He had left his hotel to go live with her in Kreutzberg. The laundry hung heavily on the line pulled between the pole of the stairs and the tall poplar, its leaves quivering. The alley’s asphalt was warped, wrinkled with frozen black waves. A filter covered the sky, where violet clouds snaked like caterpillars spinning their cocoons, wrapping Berlin in a silk he hoped was indestructible. The images needed a new setting, that of dreams. He fell asleep while listening to the falling rain.

NOTEBOOK THREE

At the age of seventy-five, Ernst Hofer was cruelly disappointed with life. His pharmaceutical laboratory’s patents fell into public property, so he could not receive any more royalties for the medicine created by Jewish chemists whose creativity he had stimulated by keeping them away from the camps long enough to harvest the fruits of his generosity. Harnessed by a few miracle remedies, these Jews had allowed him to live in luxury in his Corinthian column villa of Tempelhof, bought in 1953 from an Old South American general.

Unfortunately, the political demon still possessed him so that, during those years of abundance, instead of investing it all in Krupp or BMW, he had funded a publishing house that specialized in tales of old torturers disguised as noble heroes of the Eastern Front. But, from the Israeli grey cells, there was no juice left to squeeze. To refill his safe, he had counted on a contract with the Pentagon, which wanted to stock up on suicide pills for likely survivors of a nuclear conflict. But a senator questioned the political background of the president of the Swiss firm that held the patents. A Jew, of course! Persecution against Germany would seemingly never cease!

Hofer believed he was not condemned to poverty, but to mediocrity, like Mengele and Eichmann before their deaths, brought back to their original situation of frustrated and dull little bourgeois. He had vowed for a long time to avoid this pathetic fate, even if the price was a Wagnerian suicide that would turn his house into a funeral stake. But with age he considered surviving even on a more modest lifestyle.

In reality, he was still a multimillionaire, in dollars and in marks, but in his mind, his fortune could only decline because it was not increasing. Without admitting it, he thought his existence would not end as long as his assets remained inexhaustible. He, he thought while sighing, who had almost become viceroy of Quebec, absolute master of a whole population, would then have to end his days in a seedy furnished Kreutzberg apartment? No! He felt that his salvation would come from his distant imaginary empire when he read in a Canadian magazine, he was stubbornly still subscribed to, that the Helgoland – renamed Pickle in a blasphemous way – would be auctioned off at the beginning of June, in the Halifax port.

He remembered the microfilms he had hidden onboard so carefully, so that when they shipwrecked he did not have time to retrieve them. No one had discovered them, because the crowd he still moved in would have quickly learned about the appearance of documents from the Führerbunker.

The money he wired to O’Reilly would have raked in a hundredfold if the microfilms had not contained, after examination, unsigned trivial dispatches, addressed to the troops defending the Zitadelle Berlin. Without any commercial value on the Black Market of Nazi souvenirs. This transaction cost him a few ten thousand marks, but he came to the conclusion that von Chénier had sabotaged the microfilming operation and that the notebooks in which Hitler scribbled on his last days were still at the bottom, in the secret bunker the Russian had never detected, beneath the official bunker that they had blown up in 1947.

Found in the trunks of an old deceased GI, a photo album of the Führer’s childhood had sold for four hundred thousand dollars. And for the fake Hitler souvenirs? The Spiegel had paid six million marks. Graphologists all agreed on its authenticity: written by the Führer’s hand, with the appropriate shaking after the explosion of Colonel Stauffenberg’s bomb, they said. But no one questioned how he could have aligned entire armies of words when his tank divisions were in disarray. After some chemical and spectrographic analysis, it was found that the notebooks had been made in 1980. On Canadian paper no less.

Then came the joke between editors at the Frankfurt Fair, in October: who had spit and for how much? For a Mengele exhumed from the cemetery, what a laugh: Bormann was growing melons in Bolivia, Gœbbels on a ranch in Colorado. But how much would a handwritten and unpublished notebook of the Fürhrer sell for? Just thinking about it made him shiver with delight. There remained the delicate issue of retrieving said manuscript.

At that moment, von Chénier’s son arrived in Berlin and was yelling in the prefecture and Senate halls, demanding to know what had happened to his father forty years earlier. Through his network of old comrades of the Propaganda Ministry, he easily obtained the name of the hotel where the new owner of the Helgoland claimed he could be reached. He was tempted to order for this hornet to be squashed, for if it buzzed around too much over a few dead bodies it might sting the Canadian Press’ curiosity. Even today, an investigation on Perceval Perkins’ accidental death would bother him, especially with the absence of a protective and cheating policeman like Dansereau. Publicity, trial, deportation: the script was unfortunately too well known and often ended in Jerusalem.

But before getting rid of him, he wanted place this importune Canadian visitor to contribution. He intended to inspire himself from the terribly efficient lazy executioner’s method: asking the victim to dig his own grave. For he thought that truth was a corpse-like stillness of the last brain cell, rotting away on a sample slate under a Nobel Prize microscope.

NOTEBOOK FOUR

“What?” Christophe cried out drawing out the Prussian government agents with Fatima’s help, “You can’t find my father André Chénier’s work files? What a scandal! He worked for your government for six years. We’re convinced, my family and I, that he didn’t receive his full wages. And unless you have proof of the contrary, we will file a lawsuit to regain what is owed. We will also notify our embassy to get war compensations.”

He was bluffing. His cause, no international tribunal would so much as receive it. But he hoped to raise the bait this way. And two weeks after his arrival in Berlin, on a Sunday morning, he received

a telephone call from a certain Hofer.

“I learned, through friends of mine, that you were looking for information on von Chénier? Your father, nein? I would like to help you. I knew him a little and I called him a friend.”

He arranged to meet for breakfast at a café in the Tiergarten. Who was this Hofer? An innocent bystander, a simple colleague or the “German friend” Virginia had told him about? Impossible to know without exposing himself to danger, like an x-ray. Christophe dressed with care as meticulous as the bullfighters before the corrida. On his wrist glistened eighteen-karat wrist cuffs; he pierced his black tie with a ruby that glowed a fiery red on his dickey between the lapels of his Maxim chevron suit.

Fatima seemed intimidated; she had only seen her lover wear jeans, which her own wardrobe consisted of. Since she insisted on coming along, he used the excuse of their clothing incongruity to ask her to wait in the car. In reality, he preferred that Hofer did not lay eyes on her.

After a few minutes of wandering on the roads of the immense park behind the wheel of the Opel, he found the restaurant: a hunting lodge with wide bay windows. He parked a little bit further, behind a grove of pines.

A waiter showed him to the table where Hofer was talking into a mobile phone that was held by a chauffeur wearing a livery, immobile in front of a single cover. Raven black hair surely dyed at his age. His ink black eyes held flashes of pure ruse; he moistened his right index with his tongue and slicked his bushy eyebrows. He hung up, and then took a napkin that the other tied around his neck. Christophe moved closer.

“Herr Hofer?”

“Monsieur Chénier!”

A heavy and compact voice. On the dining room wallpaper violets slowly fell. He stood up. An American handshake rather than a bow like in the North.

“It is such a pleasure to see the son of an old friend. You look a great deal like your father. A little older, obviously, since the poor man disappeared at such a young age. Sit down and let us see if I can help you.”

As he spoke, he pinched his trumpet, broken-veined nose with its bulb-like end, and he moved his protruding chin.

“I’m trying to piece together the life of my parents who were here back then,” Christophe said. “I have undertaken the task of writing my father’s biography. Not an easy thing without documents or witnesses.”

Hofer listened, his hands on his lightly full stomach and, slipping his feet out of his loafers, he rocked himself lightly, nearly making himself fall asleep. He exhaled roughly and swallowed his drink in one swoop: a mix of cola and rye, furiously shaking the ice that was left, and the waiter hurried over with another glass.

“Prosit!” Hofer lifted his glass, studying him from behind his yellowish cornea. “And so you are interested in your father, of course. You, at the time, a little angel in your peaceful igloo… Von Chénier. Raised by your grandmother after your uncle Perceval’s death? Let us continue in French. Your German…” He sighed. “and your Canadian accent bring back so many memories. I followed your political life. Your nationalist parties: no more luck than your father in his time. Your country, we cannot catch by the left or by the right. And you? Divorced without children? The line will stop here then. A pity. Me, business is killing me, crucifying me. No, worse, because then again, that would be a normal situation…”

He spread his arms and cocked his head to the side.

“But disjointed, dismembered in grotesque positions, until the opponents make minced meat out of me. When the mark becomes flesh, what happens? An upside-down crucifixion? A swastika? You do not smoke?” His chauffeur lit a cigar for him. “So you are a translator, I think? You are making a decent living?”

“I limit my spending.”

Hofer burst into a booming laughter. “That is German humor, that. Very good!”

He stopped to pour a pink vial in his drink. “My invention. Hoferium,” he said. “A light dose creates euphoria, a heavy dose ‘euthanizes.’ Smell it!” Smells of chlorine. He blew over the vial’s opened tip. A low key. “The Pentagon will need it to spare the American population agonizing radioactive pain. Really, the Nazis were children. Now we do a lot better. With less noise, but much better. Hoferium will be the chemical wafer of the real god: death, nein?”

Outside, near the duck pond, three whores, mini-skirts slit up to their butts, were sucking their thumbs. Fatima lowered the car window. In the distance the lights of Berlin were shining up to the great shadow zone to the East. A silence.

“I cannot really give you any information. Your father worked for me, but I rarely met him, only during service meetings. I saw him again toward the last days. I had gone to the bunker to receive orders from my boss, Doctor Gœbbels, a charming man, you know, and so educated. There was no moon when I arrived. Your parents were standing at the entrance, near the ventilation tower. We had just built it to protect the ventilation system from gas grenades. With its cone-shaped roof, it looked like Méliés’ rocket in ‘A Trip to the Moon.’ Your father said to me: ‘A shame we can’t get it to take off.’

“All the Berliners wanted was to escape the surrounding. On the other hand, all our foreign collaborators, like your father, flowed back to the center, because to capture them meant the firing squad, and the chancellery defended its last perimeter with French SS from the Charlemagne division.

“You parents looked exhausted. Especially your father, whose vocal organ, that tenor one on our radio, had become a mere hoarse thread. I asked him how long he planned to stay. ‘Until the end. Actually, I don’t have a choice,’ he whispered while pointing to a guard that was keeping his eyes on us. He dragged me a bit further away and whispered even more quietly: ‘There’s a bunker beneath the bunker. That’s where they plan to wait out the storm before fleeing.’”

We talked for a while, then he hit the notebook he was holding against his chest with the palm of his hand. “I used the rest of my strength to write my memoirs.”

“Even in that end of the world decor, your mother shone so much that Eva Braun was jealous. She was worried about the winter crows that usually stopped in Berlin when they migrated that year and had almost all passed over the city without stopping. The ones that had the bad idea of landing littered the streets with their bullet-riddled bodies or they would turn into distraught and noisy swarms. Lizbeth hated herself for dragging her husband in this unfortunate adventure.”

Hofer’s eyes brimmed with tears as he seemed to hesitate, moved.

“Just before one of the guards brought him back towards the metal staircase that went underground, von Chénier said to me: “I wrote my story so that my son Christophe could learn the truth about me.” That is why, my dear, I wanted to meet with you this much: I have a message to give you…”

Slowly, the room was filling up with customers wearing Tyrolean. Schuppmann, the chauffeur, had left them, perched on a stool, his boxer face leaning over the bar made of nickel; he was gargling his Schnapps as if he was about to spit it on his reflection. Fatima was talking with one of the whores posted at the entrance of the wooden path. Christophe’s apprehension melted away bit by bit as the other presented his parents in a more sympathetic light.

Hofer looked at his watch. “Would you have a bit more time to give to a poor old man? I would like to make you visit a place that would surely interest you.”

Christophe agreed. The other folded a fifty-mark bank note lengthwise and placed it on the bill. Sitting behind the wheel of the Opel, Fatima had the reflex to ignore them when they left, but she followed the heavy Mercedes smoothly driven by Schuppmann. They stopped about a hundred meters before Checkpoint Charlie. Hofer and his guest went up a public sightseeing turret. Wooden stairs, three flights without risers, a shaky, badly sanded handrail, then a fragile platform of loose planks, soiled by the soles of visitors.

When they lifted their eyes up in the wind that brought out tears, their gaze met with the first wall and its delirium of graffiti; then, below them, the no man’s land with its barbwire and it’s anti-t

ank barricades that spiked up in the concrete dust coming from the fortifications: watchtowers in staggered rows punctuated with bay windows that reflected the clouds, sentry booths where sentinels stomped their feet.

Hofer showed him a slight hill in the forbidden space between the two walls. “Underneath, there is the Führerbunker,” he said. “The Russians blew up the access way in 1947 and they leveled the ground. In 1966, a Western Berliner dug all the way there to allow his family to escape to the Soviet side. What did he see? Hitler, with his German Shepherd he was never able to train, reading the Spiegel and watching a football game on TV, Nuremberg versus Hanover? Living without food or air, writing his apocryphal memoirs? I was a kid, of course. But if your father told me the truth, the third bunker should be hidden under there, beneath the two subterranean levels the Russians found. And I do not want to sadden you, but you will surely find the remains of your parents there, and also maybe, your father’s memoirs.”

They went back down. Some punks were roasting sausages on a grill and greeted them by nonchalantly lifting their arms. “Sieg heil!” These words, spoken in a low voice, echoed as if a crowd were cheering.

“I will be honest with you,” Hofer continued as they walked along the wall on a bushy path, littered with beer cans and yellow Kodacolor wrappings. “Your case interests me in a purely commercial sense. I have a small publishing house that is not doing very well at the moment, but that I could boost with the publication of von Chénier’s journal, as well as your tale if you are able to fool the Russians by digging a tunnel right under their noses. We, Germans, love to get revenge with pranks of the sort. Our young aviator that landed his Cessna on the Red Square gained a fortune.”

Schuppman was following them in the Mercedes. Fatima remained invisible. Had she abandoned her stalking? They arrived in front of a blue Prussian villa with three floors to let, cracked from the bad weather. Empty in expectation of a buyer that would renovate it or more likely, tear it down. Alone in the middle of a wasteland.

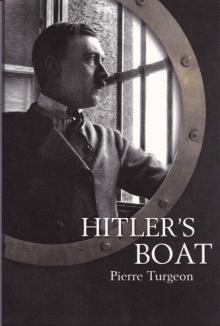

Hitler's Boat

Hitler's Boat